Your Signature Scent Says Nothing About You: Designer Perfumes as Tools of Performativity

The industry of luxury goods relies on exclusion, on perpetuating the class divide. Luxurious items are a decoration for the rich and an aspiration for everyone else. There has been a notable rise in fads, such as "stealth wealth," which aim to emulate the rich. However, designer perfumes have always existed as a keyhole into their splendor.

The top fashion houses are successful because they have crafted an allure and an identity. As The Fashion & Law Journal observes, consumers are willing to drop large sums on high-end products for "the pursuit of prestige [...], emotional gratification, brand influence, scarcity, self-expression, and […] craftsmanship." Couture is fantastical and artful, but it's made to be inaccessible. Perfume produced by these same fashion houses, however, is a relatively obtainable item that someone can buy for around 100 dollars. Perfumes are a democratized way for a large collective to participate in fashion elitism.

Paul Poiret was the first designer to launch a fragrance, but it was Coco Chanel, with the release of Chanel No. 5 in 1921, who revolutionized the fragrance market sector. Chanel No. 5 is likely the most iconic perfume of all time. As a proponent of the New Woman movement, Chanel believed in autonomous and unbounded femininity. She wanted a scent to evoke this revolution. To her, this smelled like woody florals with a clean and soapy opening, created by chemical compounds called aldehydes. The smell absolutely transfixed consumers, and, as denoted by the BBC, "[Chanel No. 5] was an intervention in the history of perfume."

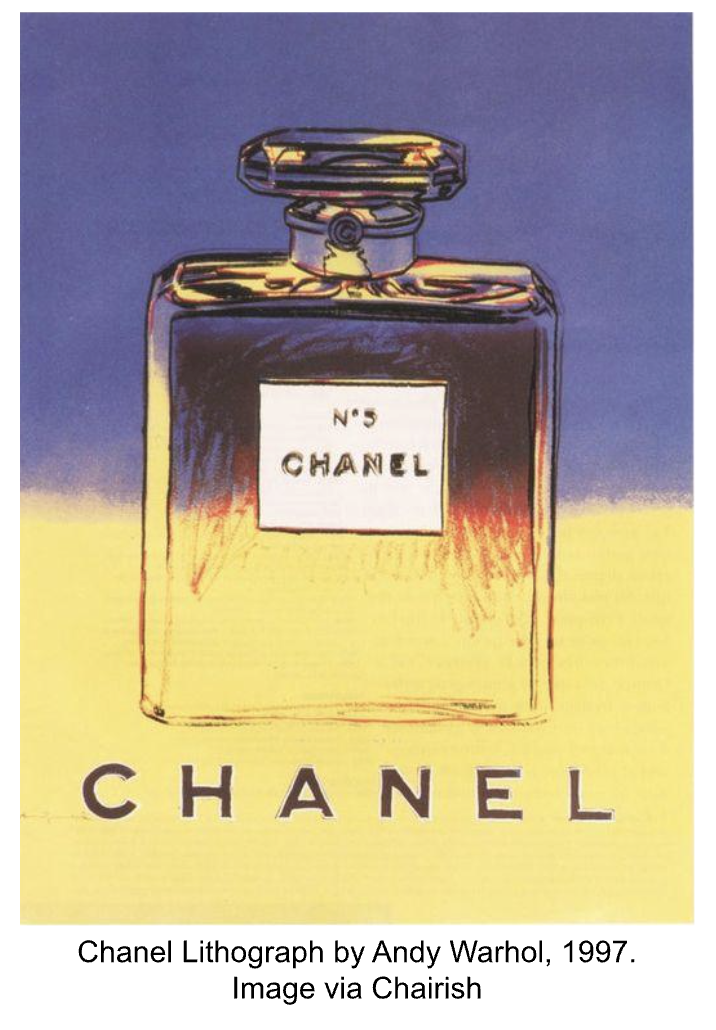

Images via The Last Fashion Bible , Chairish, and Pinterest by Charlotte Collins.

But Chanel No. 5 was more than a timeless scent; it was a character. Chanel is quoted as stating No. 5 is “‘a woman's perfume, with the scent of a woman." A statement that entirely assumes womanhood as singular; it assumes a particular scent, standardizing the aroma of a woman. Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, the perfume was advertised with taglines such as "Every Woman Alive Loves Chanel No. 5." This marketing phenomenon carries heavy implications, suggesting an absolute that is antithetical to the freedom promoted by the New Woman movement. To be a woman is to love this scent, and with a few sprays, one would become a culturally cultivated woman.

Furthermore, Marilyn Monroe, a Hollywood icon, stated that the only thing she would wear to bed was No. 5. Monroe created an exaggerated persona of herself that significantly contributed to her success. She commodified patriarchally perceived archetypes of womanhood by way of a hyper-sexualized performance. She became the face of the perfume and its significance. The idea of Chanel No. 5 becomes heavily intertwined with gender performance and synonymous with femininity. It became an expectation to indulge in this particular scent, as it would validate one's womanhood.

Perfume is a way for people to try on different roles. The human brain's olfactory psychology links preconceived patterns with smells. Referenced in Harvard Magazine, psychologist Donald Laird found that "smell can instantly trigger an emotional response along with a memory."

Smells warp our behaviors and interactions, based on past experiences we have had with the same aromas. For instance, consider Chanel No. 5. If you have always associated the scent with epitomized femininity, and marketing strategies have reinforced this perception, then that is what you will assume when you smell it. Perfumes change how one interacts with the rest of the world. Different associations and different scents will procure varying reactions from the public. If humans can change how they perceive the world through smell, then perfumes have the potential to transform a person and act as a facade.

When an obscenely beautiful woman starts whispering cryptic words on your TV, captured by overly artistic cinematography, you can assume this is a perfume ad. These are attempts to encapsulate what a designer brand wants to be conceptually. Because a scent isn't something that can be perfectly represented visually, marketing teams will manipulate consumers' class aspirations. The ads will embody exclusivity, perfection, and a sense of fantasy. By giving a scent a personality with hypnotizing visuals, consumers will be inclined to succumb to the social pressures of luxury.

While individuals have personal experiences with scents and a connection to perfume, these associations exist within a capitalist market. No matter one’s own relation to perfume, there will always be underlying socioeconomic implications of perfume. Fragrance cannot be entirely authentic.

A wearer can alter their exterior perceptions simply by switching from one perfume to the next. Perfumes are marketed to consumers as manifestations of certain ideologies; they can alter who you are. While each designer perfume has its intended performance, they all center around one desire: to be luxurious. Marketer Mathieu Arsac perfectly articulates this: "While not everyone can afford a Chanel bag, many can aspire to own a bottle of Chanel No. 5." If we purchase a perfume that conveys a sense of importance, we can adopt that identity.