So You Want to be A Showgirl, Baby.

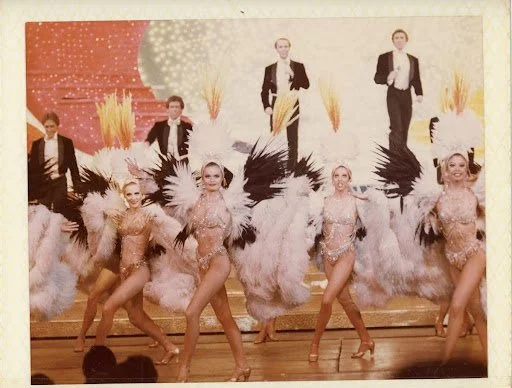

Is it a punishment to be sequined and feathered? The Showgirl is emblematic of Las Vegas, a mecca of partying, sex, drugs, glitz, and gambling. Her image is thus an expression of lawless freedom, and yet, the Showgirl has been bedeviled by exploitation. Female autonomy has often been compromised in the pursuit of good show business. The Showgirl’s aesthetics have made a resurgence in the past year. Yet the adornments of diamond-encrusted, plumaged costumes battle over whether they empower women or further encroach on their agency.

Kendall Jenner glistened on the Vogue World runway in Nicole Kidman’s Moulin Rouge bodysuit. The movie is a quintessential depiction of a showgirl. The movie's title is derived from the Parisian nightclub of the same name, renowned for its elaborate cabaret performances featuring beautiful can-can dancers.

Image via Vogue

Las Vegas showgirls borrowed these aesthetics in full; French cabarets like the Moulin Rouge established the showgirl. This year’s Vogue World showcased Hollywood’s most iconic fashions, appreciating the art and costumery of performance. However, it is curious that, even though Kidman was in attendance — indeed, opening the show — 29-year-old Jenner was the one to display the garment that Kidman, now 58, made iconic. Replacing the wearer of this costume with a younger counterpart brings up the question: how long does the showgirl have until she is replaced?

The Last Showgirl and The Substance are commentaries on ageism in performance art, questioning why a woman’s art flourishes with youth and rots as youth fades. The Substance is a science fiction film directed by Coralie Fargeat that imagines a drug that could reverse the effects of aging by creating a younger, better clone. It follows the once-famous actress, a performer and so a showgirl of sorts, Elizabeth Sparkle, as she splits into Sue with the help of the substance. In pursuit of fame, beauty, and glamor, things go monstrously awry, and the already copied Sue tries to split into another clone to achieve an even more satisfactory level of acceptance.

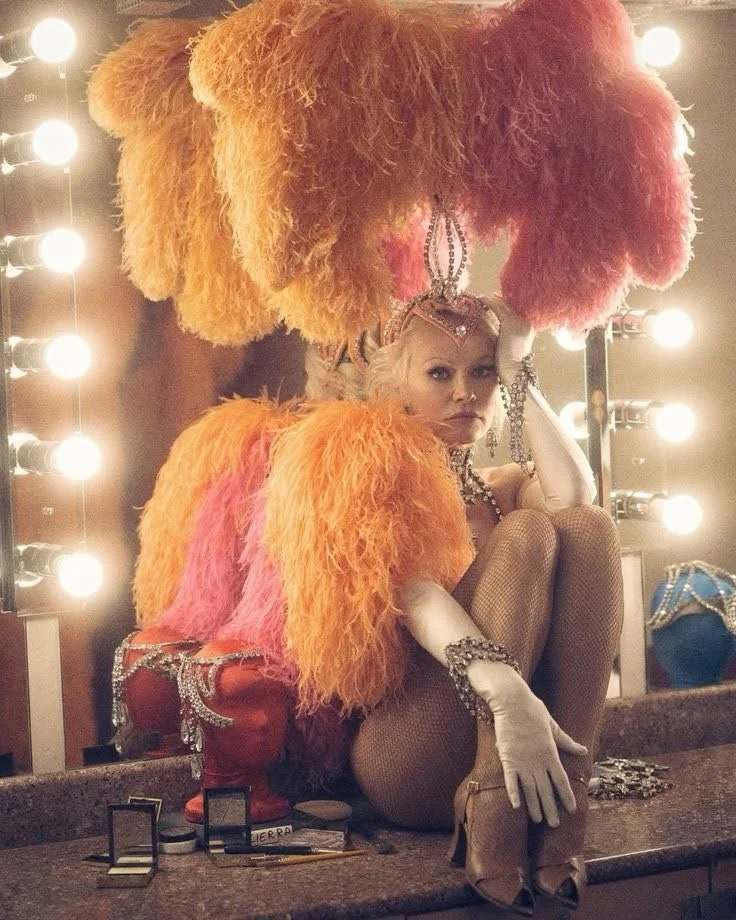

Fargeat's generous reliance on gore and body horror completes an excruciating depiction of the pains of pressured conformity to beauty dogmas. The Last Showgirl, directed by Gia Coppola, stars Pamela Anderson, advocate of natural aging, as Shelley. Shelley is a showgirl whose show is closing; she must find a new path and purpose in life as she realizes the showbiz hunts only young women.

Shelley's dependence on her job as a Showgirl is based “not just [on] the goal of being on the stage or in the spotlight, but more about feeling seen.” Performance can be manufactured entirely, and still, the rawest exhibition of yearning. So the female performer, the showgirl, is a scavenger for authenticity encroached upon by a culture fixated upon youth and beauty as social currency. It’s a devotion to performance that critics feel is lacking in Taylor Swift’s The Life of a Showgirl.

Taylor Swift, billionaire extraordinaire, has faced immense backlash for her latest studio album, The Life of a Showgirl, which is more of a worship of capital opportunity than an artistic experience. The album has just completed its 6th week as number one on Billboard's top 100. Swift's success and the album’s success are not shocking; she has dominated the charts for years and has just completed the highest-grossing tour of all time.

The song “The Fate of Ophelia” stands out as a commentary on satisfying the publicly idealized self. Swift pulls on the Shakespearean tragedy Hamlet, and the death of Ophelia, who killed herself after being driven to insanity from powerlessness. Swift, however, suggests she’s been pulled out of that fate, because of finding love for herself and her now fiancé, Travis Kelce. What makes Swift’s rendition of Ophelia so shallow is that largely what made Ophelia’s death so sad is that she was only a foil to a man. Swift litters football and Americana references all over the album and the song, crediting her resurrection to a man.

What could have been a beautiful commentary on finding one’s power in femininity and in resistance to expected performance, falls tone-deaf in a sociopolitical timeline clouded by Christian nationalism, where female autonomy is already condemned. Swift’s definition of a showgirl lies in the river beside Ophelia, performance shackled to male endorsement.

If the role of the showgirl is hollow, ephemeral, and male-constructed, then how can being a showgirl be empowering? An example of this struggle between empowerment and the male gaze is the 2025 Victoria's Secret Fashion Show.

The Victoria's Secret Fashion Show has long been criticized for being exclusionary and for promoting a beauty standard of a young, white, skinny model. In the past two years, the company has made it a point to be inclusive and have understood that the fashion industry often sets what is considered beautiful, and it is their responsibility to show that beauty is not singular. This year, the lingerie brand dressed their models in feather headpieces and performers danced around holding plumed fans, undeniably borrowing aesthetics from showgirls. Vanessa Friedman, fashion director and chief fashion critic at the New York Times, writes the VS show is “certainly not female empowerment” and “[the showgirl model is] not exactly a compelling proposition for the future.”

And of course, the showgirl as we know it will never be freed of the male gaze if white Christian nationalists are continuing to define womanhood as immobile by making policies that deprive women of full bodily autonomy.

But the VS show demonstrates some progress, responding to confining ideas of beauty, and using the showgirl aesthetic to dress women in their most vulnerable. The concept of the showgirl, of course, runs the risk of being corrupted by sexual expectation; most everything women do runs that risk as well. Showgirls are always empowering and always have been: glistening with beautiful costuming, talented dancers who train endlessly, true artists who are clouded by the patriarchy that whittle them down to objects of lust.

The resurgence of the showgirl aesthetic is causing discourse, we are feeding the ideology of female performance with a new voice, the voice of the showgirl, that counteracts the silencing force, rendering their art as being inherently sexual. The showgirl is both empowering and exploited, so it’s important to counter narratives that see her as devoid of selfhood and dependent on men —rebellion starts with reinterpretation.